Teaching Differences between South Korea and USA

Lisa Vinish, a Reach To Teach teacher from Alberta, Canada, recently had a chance to sit down with her employer in South Korea to get her thoughts on educational differences between Korean and US schools. Lisa’s first teaching job was teaching with EPIK in 2010, but now she teaches at a private Montessori kindergarten. The person she interviewed for this piece is her current employer, who lived and taught in the US for nearly two decades and has been running her own school in Korea now for about five years. Her employer has a lot of insight and Lisa thought it would be a good idea to share what she has to say with a wider audience.

How many years did you live and teach in the United States?

I lived in the US for just under 18 years. I moved there in middle school and stayed throughout high school, University, and started a career in early childhood education. I had five years of teaching experience in a Montessori education system before moving back to Korea.

Can you briefly describe the Montessori education philosophy?

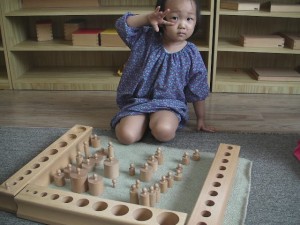

It’s very difficult to explain traditional Montessori philosophy in a nutshell, but basically it centers on respecting the child’s independence and natural process of learning. Self-discovery is key. The educator creates a hands-on environment in which the child is free to explore. Learning occurs through the handling of materials and not necessarily through direct teacher-student instruction. These materials, or jobs, are carefully prepared and each one has a specific purpose in contributing to a child’s physical and psychological development.

Does the Montessori model work in Korea?

I think the traditional model doesn’t work well because it doesn’t mesh well with the culture. Parents will initially embrace Montessori schools because it is a new concept to them, and anything new is trendy. However, after a couple of years the novelty and enthusiasm wanes. In the first couple of years, my school constantly had new enrollments. But these days it’s been more of a battle to sign up new students. Also, the Montessori approach encourages individualism. Korean culture does not embrace individualism so I think that’s another reason traditional Montessori schools do not take off like regular kindergartens or hagwons.

What do you think are the main differences between American and Korean learning and education styles?

To me, they are total opposites. But I do want to emphasize that I’m basing this judgment on my own personal experience as an educator. That being said, in the US learning is considered to be a long process of development. It incorporates methods of learning that trigger a child’s five senses. There is no strong push for studying around the clock, at least not until high school and University. The focus of early childhood education is learning through play, and it’s important to make mistakes and learn from them.

In Korea studying is pushed from an early age and learning through play is simply not considered learning. I’d say the push for education becomes very evident to the student by second or third grade. Learning isn’t seen as a slow and nurtured development process. Rather, the goal of the parent is for his/her child to “get it”, the faster the better, and the only way this can be achieved is to make sure academics are the focus of the child’s life. There is little flexibility in their schedule for play or fun extracurricular activities. Most Korean kids attend hagwons after school (which are private academies focused on one or two particular subject areas). These hagwons are not just for school age children. Some parents of 4 and 5 year olds will have their kids registered in 3 or 4 different hagwons, ostensibly to get a “head start” in education. Some parents push their kids because it is trendy to do so. It’s not uncommon for parents to register their child in a hagwon simply because “so and so’s” child is registered.

In what ways are American and Korean students different?

In the US, my students had so much confidence. Even if they didn’t have the ability to do something, they at least had the confidence to try. In Korea, kids are generally more stressed out. I notice it in their body language; their shoulders are slouched instead of straight, and their gaze is fixed to the ground. They were never encouraged to make mistakes, quite the opposite in fact. Mistakes are to be avoided as they are a sign of failure. They’re afraid of getting an answer wrong on the first attempt; therefore, they don’t try. It’s very difficult and sad as an educator to see this. That’s why we need to try to lift them up and remind them that the word “mistake” means opportunity, and is not synonymous with failure.

In America, my students’ parents were interested in knowing how their child was developing socially, behaviorally, and then academically. Whereas in Korea, the parents show more concern with how their child is performing academically. The biggest complaint of Korean parents is that I’m not pushing their kids hard enough academically. Again, it’s the mindset that learning is not a long process of development, but rather, a light bulb turning on resulting in the sudden mastering of reading, writing, speaking, and listening.

Some parents also deny or ignore their child’s limitations in order move him/her up to the next level. In these cases, the student suffers a loss of confidence because they don’t understand the material they’re having to do. We feel good when we do things we’re good at. If the student isn’t good at English or Math because they’ve been prematurely passed on to the next level, that student is obviously not going to feel good and there will be a drastic loss of self-confidence.

It’s also very difficult to bring up issues in regard to learning disabilities. In the US, parents would want to know right away of a teacher sensed a learning disability, and if it was suspect, that child would undergo immediate testing to confirm and then an appropriate remedy would be sought. Parents and teachers in the US are more proactive about diagnosing and treating such disorders. In Korea, again this is from my personal experience, parents are not open to the prospect of learning disabilities. And whenever I have brought up worrisome cases, parents reacted by denying the possibility. And in the cases parents agreed with me, they simply didn’t take the problem seriously. They either believed that the disability was a charming “quirk” and cute, or that he/she would eventually grow out of it.

What was the biggest surprise or challenge to you during your first couple of years as a director and educator in Korea?

The over-involvement of parents. I was not expecting it to be so challenging to get parents to trust my approach and take my concerns seriously. Overall, I don’t think the word “surprised” describes how I felt; rather, I think it was disappointment. This is not the Korean education system I remember growing up in. It has changed so much in the last two decades.

If Korean parents and students were to take one thing away from their time at your school, what do you hope it would be?

I want parents to walk away knowing that sending their child to my school was a good decision. My hope is that they feel they did something positive for their child’s development. My goal as an educator is to find each students’ strengths and weaknesses, then take their strengths and use them in a way that will allow them to learn English more effectively. My goal is to reduce or eliminate the stress associated with learning another language. I would hope that they walk away from my school more confident than when they arrived, and with a genuine love for English.

2 Responses

I am interested in working in South Korea, for a Montessori school. Is there any way of knowing if this school needs English speaking assistants?

Hi Sara, You would need to apply through our job board and then we can see if there are any school that you would be interested in.